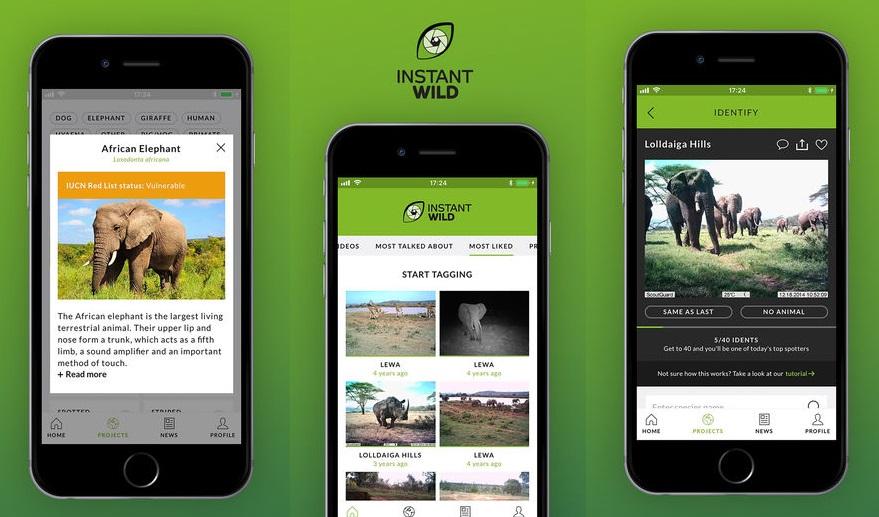

To provide a live video stream from the wild using a cellular camera was one of the key challenges for ZSL’s new Instant Wild app (below). As with other Instant Wild cameras the backhaul connection would have to be cellular to cope with the high bandwidth streaming a video requires. The camera would have to survive in a remote (but cellular connected) field location, require little battery maintenance, be simple to set-up and preferably do all this at a reasonable cost. It was a more difficult task than it sounded.

Idea 1: Off-the-shelf video capable Trail Cam

Our first thought was to use a cellular trail camera that took videos. Simple. However, although most trail cameras specify a video mode, most camera don’t actually transmit them, they are just stored to internal memory. This is due to the high amount of data transfer and battery consumption doing this would incur. By speaking to some very supportive and helpful trail camera retailers in the UK we heard that there might be one trail camera manufacturer that could provide this cellular video transmission solution. It was called the Stealth Cam GX45NG. So we got one to test.

It was more expensive than most cellular trail cameras we normally use and online reviews were not great, mainly suggesting that although a brave attempt, Stealth Cam hadn’t quite cracked the video transmission challenge yet. Our testing found this to be true, with video transmission being unreliable, the camera being complicated to set-up correctly and the videos transmitted to an app and not an email address. Our main problem was with the app which was glitchy and seemed focussed at the deer hunting market.

Idea 2: Security style IP Camera

Next I looked for security style Internet Protocol (IP) cameras being used in remote locations like construction yards or marinas. The trouble with these cameras was their high power usage as they were designed to use power over Ethernet (POE). A number of companies were offering a cellular connected battery powered IP camera as a bespoke security solution. This was done by connecting an IP camera to a cellular modem placed together in a large enclosure with a big 12v rechargeable battery that connected to a 20 watt solar panel.

Although a seemingly workable solutions we had a problem as these cameras were:

- High cost (the cheapest offer being £1500);

- High power consumption (10 watt) requiring large heavy batteries and solar panels;

- Very intrusive, requiring heavy duty mounts and set-up to install them securely which would have blighted any natural landscape.

With these IP camera the triggering and wake up speed was the next problem to solve. The companies I looked at had all approached the problem slightly differently. Most would just record and transmit at timed intervals. Some had added on-board image recognition, meaning that although the camera was on all the time, it only recorded and transmitted when a movement detection occurred in the video feed. Others had tried to incorporate PIR sensors but these didn’t appear well tuned to the camera field of view and would likely be triggered by minimal movement events. We really wanted our live video camera to function as a trail camera, i.e. being in a low power quiescent state until a sensor, triggered by an animal, wakes the camera up and makes a short recording.

Breakthrough: Discovering Arlo Go

But then a breakthrough happened on one of my regular trips to our local Maplin. There I found a wireless security system with battery powered cameras connected by wifi to a base station. This set up was made by a company called Arlo, a subsidiary of Netgear. I started to research their cameras online to see how I might adapt one with a cellular modem and, lo and behold, they have already done it and called it the Arlo Go!

What’s more, it had been available in the USA for the past year which meant that a lot of the initial teething bugs had been documented and fixed. Arlo Go had yet to come to the UK but a UK version was being built. After frequent calls to find which US model would work best in the UK and having made friends with their very friendly customer services department we were very fortunate to get an early UK model to try out. Thank you Arlo!

Intital Tests: ZSL, UK

The Arlo Go is about the size of a tennis ball and is extremely simple to use with really only one button on the camera body.

The first thing to do was to stick in a pay as you go data SIM, download the excellent Arlo app and insert the cube-like, very high power density battery. The camera is then cleverly synched to your app and creates an Arlo account by the camera scanning a QR code displayed by the app. The set-up and control of the camera is then all performed by the app through a cellular connection.

Once set up, we got to work testing the camera behind the lion enclosure in the zoo. To our delight (and relief) it did exactly what it said it would, and more.

The app allows a full range of configuration options and video lengths and even more remarkably you can remotely turn the camera off and on. We decided to add a small 2 Watt Arlo solar panel to trickle charge it, although this wasn’t much good during our testing late last year as the sun in November in the UK is fairly elusive. A full testing report is available on request.

Field Tests: Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Kenya

Confident that we understood the camera and it’s abilities from our testing, we took it out to Kenya to install it at the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy - a long time supporter and close friend of Instant Wild.

Lewa is always an amazing place to visit and in mid-November it was completely green and lush with long calf high grass providing plenty of grazing. The Lewa research team are so supportive and forward leaning to the use of technology that it didn’t take long to brief them on the Arlo and get them excited. Ian Lemaiyan, the man you may have seen on a motorcycle on the Lewa cams on Instant Wild, was to be my partner for the camera install and we set out with a fencepost and some tools to a location where an elephant fence line and a marsh creates a natural wildlife corridor.

We banged in our post for the camera and solar panel mounts in the shelter of a large fallen tree that we hoped would provide a natural barrier to prevent animals coming too close to the camera. We screwed in the mounts, securely zip-tied all the cables and then camouflaged the camera and panel as best we could using camouflage netting scarf from an army surplus stall in Camden. The camera was set to send us a push notification on every trigger event and we could see from the app the camera was solar charging. Everything was perfect. We left the site and went back to camp eagerly awaiting our first animal video.

The first few videos received were greeted with excitement, an impala and a couple of waterbucks walking down the trail. The next day after a slow morning of several clips of a crested crane that seemed to enjoy the area we started getting clips of a herd of elephants. It was amazing and secretly exactly what I had been hoping for. Nothing is more impressive than wild elephants roaming across the African landscape.

But then came the first sign of trouble.

An elephant tusk appeared in the field of view and the camera was severely bumped. Then a second younger elephant came up and started pulling at the camouflage netting with it’s trunk.

It was great footage but I was worried for my Arlo. We went back to the site and could see that an elephant had used our post for a bit of scratch.

At this point I contemplated making an additional housing for the camera and panel but rejected the idea when I realised that this would make the whole system much larger, complicate the aiming and positioning of the camera and panel and likely interfere with the cellular reception. To try and discourage elephant attention again we carried some large uneven boulders to the post and made a platform of rocks around it. Apparently elephants don’t like standing on uneven rocks so this should be enough to deter them from coming in close and send them to an alternative post for a scratch. We collected as many rocks as we could find in the area and made a scattered ring out to about 1.5 metres from the post. In retrospect we should probably have gone away and collected even more as it is recommended to have a dense ring of stones at least a 3 metre in radius.

The next day the real disaster struck. I was working on something else when a video notification came through to my phone. I opened the video to see an elephant’s mouth approaching the lens and then an intimate view of the elephants face as the camera was ripped from the post, all accompanied by squeaking as the mount was ripped apart. The brave little camera sent this final video and then nothing more. The connection had been lost. RIP Arlo, I thought. Ian immediately rang me and we jumped in our 4x4 and went cautiously to the sight in case the elephants were still around.

As we got to the sight devastation greeted us. The post was hanging drunkenly at a crazy angle with the solar panel dangling from it’s cable in the breeze. The camera was gone! As we got closer I could see the camera sitting in the grass not far from the post, it’s camouflaged skin disguising it from further harm. Relief!

On initial inspection the camera seemed to be ok but the metal screw plug had been torn from it’s base straight out of the plastic casing. It was still screwed to the mount. The solar panel was also still intact but the elephant has pulled the aluminium ball sock clear out of the mounts housing, splitting the metal in the process. The real casualty was the solar charging cable micro USB connector that had been in the camera. It had been twisted as the camera was removed. It all seemed fixable and I was so relieved that the elephant hadn’t just wandered off carrying the Arlo, otherwise that might have been it for the project.

Elephants destroying conservation technology is nothing new and I have spent many hours in the field setting up tests only to find that in the night an elephant has decided to play a game of let’s pull this cable. I’m not an elephant psychologist but my best guess is they just want to see the world burn!

Not one to be beaten by a bit of elephant damage we recovered the post and set to fixing the equipment with superglue and pliers. An afternoon test was enough to show us that the camera and panel were still working and the next morning we headed out again to a spot near to the original site. This time we placed our camera post just within the electrified elephant fence, directly in front of a large fallen tree that would act as a barrier from behind. We then wrapped the post in bark to make it blend to the background and rubbed buffalo dung all over it to camouflage the scent. This seems to have worked although it took quite a while to make the mounts as stable and firm as they were before and they will have to be replaced when spares can be delivered.

It is ironic that after all the technical challenges of deploying a cellular video camera in the field: power, signal, maintenance, triggering, etc; the hardest thing was to prevent the animals it is designed to watch from destroying it. The camera is still in position and working beautifully capturing some great clips of wildlife coming through. We even had a visit from the same elephant herd who spent a number of hours grazing in front of the camera obliviously so it seems the camouflage and smell masking has worked.

I would like to thank Lewa Wildlife Conservancy for all their support of this deployment and in particular Ian Lemaiyan who is a real frontline hero. A big thank you to Arlo and in particular their customer support and technical team who have supported us throughout our project.

And finally, if you want to see some videos from the described site just go and download the Instant Wild app.

About the Author

Sam Seccombe is the Field Specialist in the Conservation Technology Unit at the Zoological Society of London. He is currently working on Instant Detect and spending time in Tsavo West in Kenya testing and trailling new equipment. Sam studied Zoology (2.1 Hons) at Bristol University, specialising in animal behaviour and previously spent 4.5 years in a front-line reconnaissance Regiment in the British Army, leaving at the rank of Captain.

Add the first post in this thread.