For the men and women on the frontline of wildlife protection, real time data dashboards are changing the way they manage their resources and respond to potential threats. Using technology that’s not unlike a system used by the New York City Police Department to tackle crime, protected area managers are organising and visualising data to keep track of their assets and deploy resources more effectively.

One of these dashboards is the Domain Awareness System (DAS), a tool developed by Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen’s Vulcan Inc. for park managers who are overwhelmed by data. Currently installed at five sites across Africa, with six more installations planned by the end of 2017, DAS is already generating alerts that have led to action. But, perhaps more significantly, the groups who are part of this project are talking more and sharing information with each other — an extremely pleasing outcome for DAS’s lead program manager, Ted Schmitt. Curious to learn more about the growing role technology has within protected area management, I spoke to Ted one Friday afternoon over Skype.

“Technology allows us to see the problem, raise awareness, and scale up the solution,” said Ted when I asked him to explain the role of technology in conservation. “When I spoke to park managers, they told me they were overwhelmed with data, so we built a platform that organises it all.”

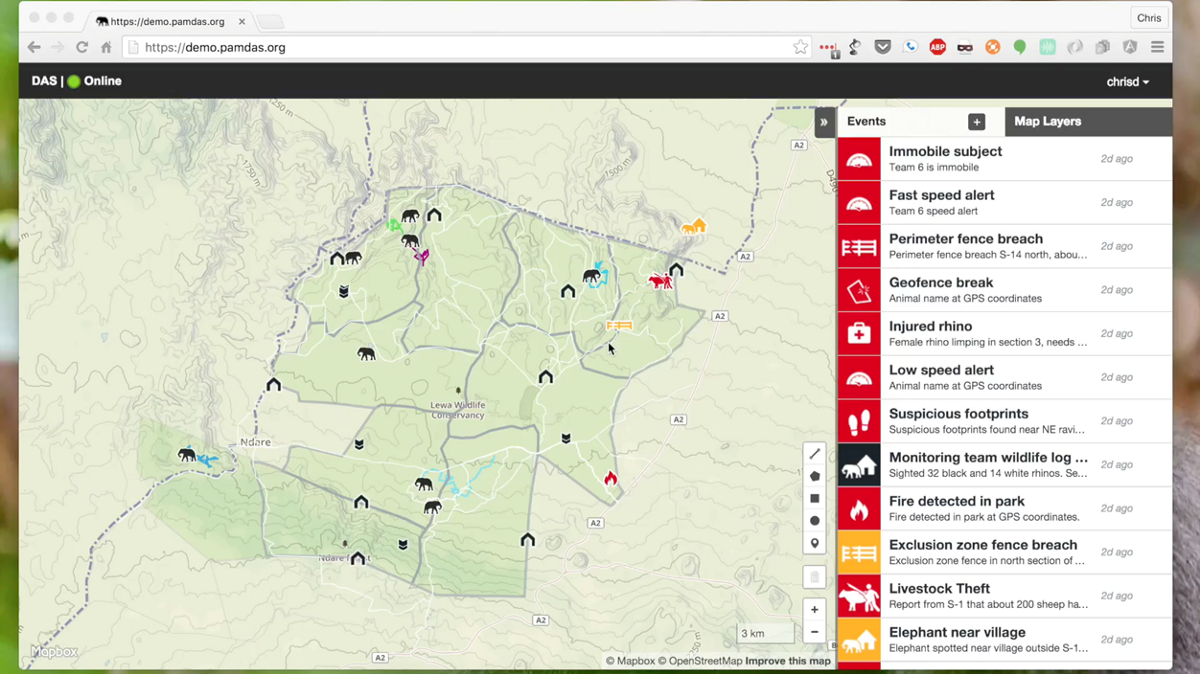

Now, with the help of DAS, managers can view the position of radios, vehicles, aircraft, and animal sensors within a protected area on a map in real-time, and all their data is organised in a manageable way. An added benefit of visualising the data in one place is that is has made it more apparent to anyone working in protected area management what additional data would be useful to have.

A screenshot of the DAS demo which shows what kind of information can be entered and displayed on the map. © Ted Schmitt

Collecting more data will be crucial for protected areas managers to take advantage of the next big step in technology — machine learning. “You need a lot of data for machine learning to reveal anything interesting,” said Ted, “but in the future when we have more data, I hope we’ll be able to detect patterns we haven’t seen before. For example, the system will be able to detect if an animal or vehicle is moving erratically and issue an alert for a human to act on.” Although it may be a way off yet, the idea of being able to detect patterns that predict when poachers might strike must be very appealing to park managers. Ted hopes we can apply the rapid advances in sensor technology—which is driven by the commercial uses of Internet of Things—to conservation.

Acknowledging that we aren’t quite ready for machine learning yet, I asked Ted if he saw any particularly cool tech being demoed at the 28th International Congress for Conservation Biology (ICCB), which he’d recently attended. He replied that he was impressed by new technology-based tools such as eDNA — which targets illegal wildlife trade passing through international ports — and acoustic sensors. Ted thinks these acoustic sensors have potential applications in DAS, and he described how they could be used as an “electric geofence” that would tell you when an elephant crosses into dangerous territory.

Human-wildlife conflict is a major issue in many parts of Africa. As our human population grows, the competition for land intensifies between humans wanting to convert the land around them and the wildlife that already occupies the spaces we’re moving into. One of the hopes for DAS is that it will be able to reduce this conflict by alerting rangers when an elephant, or other large mammal, crosses park boundaries and moves too close for comfort towards farmland or a human settlement. With timely alerts, it’s conceivable that park rangers will be able to mobilise quickly enough to shepherd the creature away from the firing line, protecting the animal, crops, and human lives.

However, Ted did have a few words of caution about using technology to solve conservation problems. “With the aid of technology you can take data and present it in compelling ways and raise awareness, but if people don’t care, or deal with the root of the problem, then technology won’t help. I saw many exciting ideas at ICCB, but we need to find a way to use these ideas at scale, and they have got to be cheap and easy to use. There’s not a lot of money in conservation so providing solutions that are sustainable, both economically and in terms of capacity, is incredibly hard.”

Domain Awareness System (DAS) Provides Real-Time Tools to Protect Threatened Species

What is apparent though is that DAS is proving to be a sustainable solution. “Having a common platform is a mechanism for sharing information,” said Ted. “Since DAS was launched, groups have settled on a common protocol for presenting data which is a huge win for conservation.” DAS isn’t just helping individual parks manage their own resources, it’s encouraging them to work together and share their knowledge so they can all benefit from each other’s best practices.

So, what’s next for DAS? “Stay tuned,” says Ted. “The foundation is in place, and with the support of Paul G. Allen behind it, we’ll continue to build upon it. Since we launched DAS in October 2016, thirty more sites have expressed interest in installing it and I’m excited about the future. It’s a dream job for me, combining my love for wildlife with a professional interest in using tech for impact, to overcome barriers in conservation.”

As I wrote up my conversation with Ted, I mulled over these last words and considered more deeply how the engine of technology is powered by passionate people. Solutions achieve success because people care about the issues they are tackling, and technology is a tool they can use to create a bigger impact. When people are given the opportunity to come together and share their skills and expertise, we can create change that is greater than the sum of our parts. Technology has an important role to play in our efforts to protect the wildlife and places we love, but the solution has to begin with us.

I’d like to say a big thank you to Ted for talking to me about the Domain Awareness System and Vulcan Inc.

About the Author

Camellia Williams is Vizzuality's lead writer. It's her job to raise the level of debate about using digital products to improve our world, through all of vizzuality’s communications. They brought Camellia on board as our first dedicated communications specialist to uncover the best ways to captivate audiences with stories that matter.

From the smallest fish in the Great Barrier Reef to the lowland tapirs of the Pantanal, Camellia has been giving a voice to the species and ecosystems we all depend on for survival for nearly five years now. She’s worked for a number of NGOs and inter-governmental organisations in that time, inspiring sustainable behaviour in the public and policymakers by communicating high-quality science. She also has a Masters in Conservation and Biodiversity from the University of Exeter to boot.

If she’s not writing about nature, you’ll find Camellia out and about snapping pics for her carefully collated instagram. Rumour has it her spirit animal is Channing Tatum, but her dance moves are more Joey Tribbiani than Magic Mike.

This piece first appeared on the Vizzuality blog on Medium, and was republished here with permission.

Add the first post in this thread.